Good business decisions cannot be made with bad data. At Uber, we use aggregated and anonymized data to guide decision-making, ranging from financial planning to letting drivers know the best location for ride requests at a given time.

But how can we ensure high quality for the data powering these decisions? Interruptions in the pipeline can introduce troublesome anomalies, such as missing rows or fields, and affect the data we rely on for future decisions.

Conventional wisdom says to use some variant of statistical modeling to explain away anomalies in large amounts of data. However, with Uber facilitating 14 million trips per day, the scale of the associated data defies this conventional wisdom. Hosting tens of thousands of tables, it is not possible for us to manually assess the quality of each piece of back-end data in our pipelines.

Over the years, teams at Uber have built several services to help assess data quality, from monitoring various metrics to enabling engineers and data scientists to create customized tests for each data table.

To this end, we recently launched Uber’s Data Quality Monitor (DQM), a solution that leverages statistical modeling to help us tie together disparate elements of data quality analysis. Based on historical data patterns, DQM automatically locates the most destructive anomalies and alerts data table owners to check the source, but without flagging so many errors that owners become overwhelmed. This new approach has already proven valuable for teams across Uber. We hope our work and the insights we gained will benefit others working with similar volumes of Big Data in the future.

Uber’s Data Quality Anomaly Detection Architecture

Ensuring high data quality for Uber’s complex and dynamic business infrastructure required leveraging all our existing tools, including Argos and the processes that surface data metrics to Databook. Our primary goal in building this anomaly detection architecture was to automate data quality monitoring. At Uber’s scale, manually combing through such large volumes of data would be untenable. We must cut down on the need for human intervention as much as possible.

With minimal manual direction, DQM tells us whether current data varies from what we would expect given past observations. DQM characterizes data tables historically to assess data quality as well as any high-level changes. For instance, if the number of rows in a given data table drops drastically between one month and the next, then we know a data quality issue probably occurred. DQM allows service owners to understand whether incoming data adheres to historical patterns prior to setting up computational parameters for downstream data analysis pipelines.

When anomalies are present, the data user is warned to proceed with caution in downstream analyses and modeling. It is vital that data scientists and operations teams know that data is trustworthy beforehand, as many business decisions are made with dashboard-based pipelines that are constructed to be holistic yet concise. While easier to understand, these dashboards are not designed for daily manual monitoring and intervention of the underlying data itself. As a result, dashboard-based pipelines may lead to poor decision-making when anomalies are present but hidden. Fortunately, by identifying such anomalies, DQM prevents these degradations from impacting our services.

Figure 1, below, depicts how we connect DQM with data sources and a front-end UI for our data quality detection system:

Data quality metrics are the foundation of our system. At Uber, our in-house metric generator for DQM is called Data Stats Service (DSS). DSS was built to query any date-partitioned Hive and Vertica table to generate time series quality metrics for each table column. For numeric data, we look at metrics including average, median, maximum, and minimum. For string data, we obtain metrics including the number of unique values and the number of missing values. The more general the underlying features, the better the system works across Uber’s entire product space.

The front end of our complete data quality detection service is a Data Quality Platform, a general tool that allows data table users to perform data quality tests through an intuitive dashboard. These data quality tests are query-based; for instance, we can test whether the number of missing values exceeds a certain threshold over any given period. Whenever a test fails, the dashboard raises an alert and the table owner receives an email regarding the test failure. A suite of tests can be set up through the dashboard to achieve wide coverage. Depending on the failure patterns of these tests, the data table owner may gain knowledge about the possible root cause.

Tying the data sources to the front end dashboard is DQM, which analyzes incoming data from these sources and scans for anomalies before it’s surfaced in the dashboard. Complicating the task is the fact that the DQM needs to cover all product areas at Uber, meaning it needs to be general enough to handle diverse conditions. Different data tables have different seasonality patterns, and some data tables may not exhibit patterns that can be defined as normal.

As the size of the data increases, so too does the number of potential data issues. At the end of the day, we need to be able to consistently address this question: did the current day’s data look normal and, if not, how do we point our users to the abnormal data metrics to fix the system pipeline? We surface this information in the form of a quality score as an automated test on our Data Quality Platform.

The statistical methodology behind DQM

To power DQM’s ability to flag abnormal data tables, we leverage a traditional statistical methodology that helps us develop an understanding of historical data patterns through analysis and compares them to the current data being tested.

For each data table, DSS generates a multi-dimensional time series output. This can be useful for smaller tables, but for very large tables the number of time series becomes unwieldy. How do we go about turning this kind of data set into actionable anomaly alerts? How do we perform anomaly detection? And how do we establish a standard of scoring that works for different use cases across the whole of Uber? In short, we need to map our complex problem into a simpler one. Then, in the simpler space, we come up with a scoring strategy to measure data quality.

Projection of multi-dimensional time series data

The first problem we face involves dealing with the multi-dimensional nature of data quality metrics. We need an efficient way to condense our data to reveal historical trends and patterns. Monitoring the evolution of a data table and its variations over time helps boil quality metrics down to a single anomaly score.

To facilitate our modeling, we treat each table’s metrics as bundles since columns of data tables are recorded together via correlated events. For example, trip duration correlates with trip distance. Due to the intrinsic relationships between columns, we can perform principal component analysis (PCA) to decompose the evolution of many metric time series into a few representative bundles for more scalable computation downstream, as depicted in Figure 2, below. Since correlated time series may have the same underlying seasonality, the representative time series also exhibit this seasonality pattern.

After bundling hundreds of metrics through PCA, we obtain several principal component (PC) time series, key composite metrics that essentially represent the entire data table. Of these, the top-ranked PC series explain more than 90 percent of the variation in the data, so visualizing them allows us to inspect table-level behaviors. For example, in the data table visualized in Figure 2, above, we observe that the second PC (or PC2) corresponds to the days of the week.

This same correlation exists in the underlying metrics that constitute PC2, but is harder to see with the data in its raw form. Analyzing top PCs is especially powerful for tables that have more than two months of history because we can capture state-shifts, such as changing trends and seasonalities, as depicted in Figure 3, below:

Whenever we observe a break in a seasonal trend, it is likely that the data pattern changed as well—perhaps because of missing data values, incorrect data recording, or a change in the schema of a data table or its ancestor.

Anomaly detection setup

After bundling our data table metrics, the second challenge our DQM tackles is to actually perform anomaly detection in these projected PC times series.

One-step ahead forecasting, which means only predicting the next step in a time series, is the solution. We use the prediction interval to validate whether the current one-step ahead value adheres to historical patterns. If not, then we have an anomaly. While there are many time series models, we focused on the Holt-Winters model, as it is simple to interpret and works very well for forecasting problems. In particular, we utilize Holt-Winters’ additive method in modeling our time series data. The setup for the components of the model is as follows:

The one-step ahead estimate, ŷt + 1 | t, is based on three underlying components: the level lt , the trend bt, and the seasonal term st. A useful property of this setup is exponential smoothing, wherein the most recent point has more influence on our prediction than the previous points.

While exponential smoothing creates a bias against old data in favor of new data, it is very helpful for two reasons. First, our business evolves very quickly due to various economic forces and constraints, such that the data patterns we see today may soon become—quite literally—a thing of the past. Second, as it is difficult to remove anomalies or anomaly-like patterns (i.e., holidays that fall on different days each year, and affect rider demand) in our complex systems, it is desirable to downplay local trends; however, our seasonal components still help our model remember past seasonal trends that are the hallmark of our business.

Uber’s Argos Platform powers our back end anomaly detection runs, and we plug into this platform to complete our methodology setup. To validate our methodology, we first perform backtesting on hundreds of data tables sourced from across Uber. Since we are performing one-step ahead validation for each PC series, we need to do projections twice—once without the latest data point and again with the latest data point, as any drastic change in the latest values of the bundled time series can shift the projected result. In a way, we want this behavior, as any drastic change in the latest data point can be amplified by this projection strategy, which helps us in our search for data quality issues.

Table quality scoring based on anomaly patterns

At this point, anomaly detection is done. However, we needed to standardize our anomaly scoring system and come up with an alerting strategy for the DQM to work with tables from across Uber’s myriad departments. Most importantly, we wanted to prevent overwhelming data table owners with alerts when no action was required.

In our implementation, the anomaly score is established by how far the most recent date’s PC values are from the forecast values, given several prediction interval widths. The interval ranges determine the severity of the deviation, from zero (normal) to four (extremely anomalous). A data table’s overall anomaly score for a given date is the sum of anomaly scores for all three top-rank PC time series.

With this methodology, each PC time series’ contribution is weighted the same, even though each PC series explains a different percentage of the table metric variation. We decided on this unweighted scoring system to help bring forth anomalous behaviors that might otherwise be disguised by the larger variations in higher PCs. On the other hand, having too many PCs in this scoring system would lead to inaccurate or misleading scores.

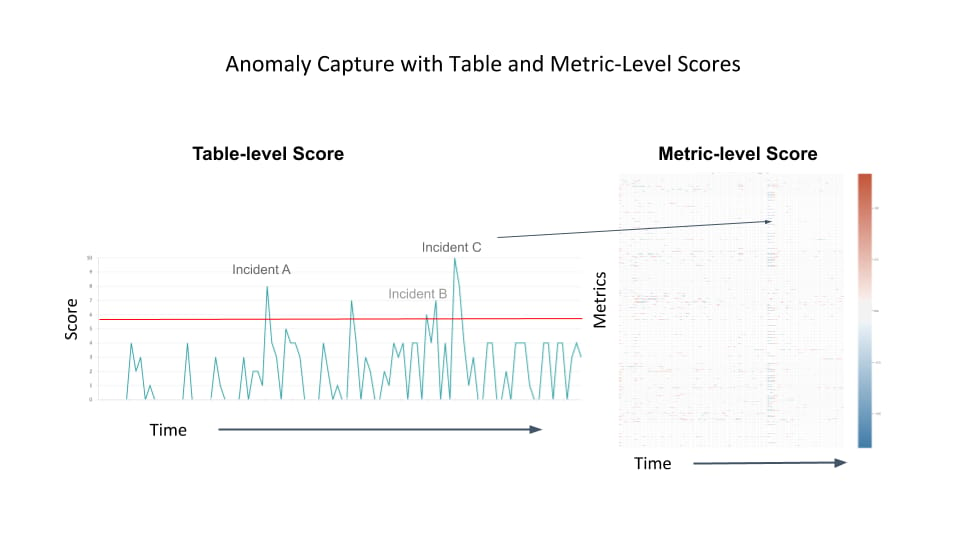

By applying this anomaly detection processing to our Big Data infrastructure’s onboarded Vertica and Hive tables, we are able to visualize the overall likelihood of anomalous behaviors for clusters of tables over time. As such, we have observed that data table-level alerts under DQM are much rarer than traditional metric-level alerts, lessening the chance of data engineers experiencing alert-fatigue. Generally, we recommend following the table-level alerts based on historical patterns in addition to a curated selection of metric-level alerts. When any of these alerts fire, the user can then reference other tests to determine whether data quality has degraded, as depicted in Figure 4, below:

DQM implementation

To easily plug DQM into Uber’s Big Data ecosystem, we built our back-end component using PySpark. PySpark enables DQM to establish API calls to existing platforms, convert the input data into the desired format, implement the underlying statistical methodology, and output results into HDFS.

Once we calculate the table-level and column metric-level quality scores, we perform downstream visualization and data science work using other tools, such as surfacing tests on the Data Quality Platform. This is our connection from the back end to the front end of the complete monitoring system.

On the front end, users receive the data quality scores daily, and can set up additional quality tests to work in concert with automatic scores generated by DQM’s statistical computations. For example, when a data issue occurs, our automatic test triggers an alert on the data quality platform. After receiving the alert, the data table owner knows to check the quality tests for potentially problematic tables and, if many tests and metrics are failing, they can proceed with root cause analysis and outage mitigation.

Next steps

Since putting Uber’s Data Quality Monitor (DQM) into production, the solution has flagged data quality issues for various teams across the company, facilitating better services for users worldwide.

We hope others in the industry find our approach to data quality monitoring useful, particularly organizations working with quality issues at the petabyte scale and beyond.

We are expanding upon this work by making our service’s root cause analysis more automated and intelligent. These improvements require additional data, such as lineage of tables and columns, as well as bundling of metrics into more action-interpretable features. During experimentation, we observed that by clustering our data quality scores through time, we can spot similar data tables with a similar quality degradation, which suggests the propagation of common anomalies through the data pipeline. We can then use these similarities to identify potential breaking points in our complex processes.

Acknowledgements

This project was a huge collaboration between many teams at Uber. We want to thank our collaborators, including Kaan Onuk, Lily Lau, Maggie Ying, Peiyu Wang, Zoe Abrams, Lauren Tindal, Atul Gupte, Yuxi Pan, Taikun Liu, Calvin Worsnup, Slawek Smyl, and Fran Bell.

Ye Henry Li

Ye Henry Li works as a data scientist on Uber's Platform Data Science team.

Ritesh Agrawal

Ritesh Agrawal is a senior data scientist on Uber's Data Science team, leading the intelligent infrastructure and developer platform teams. His work is focused on finding innovative ways to use data science and AI to make Uber’s infrastructure more adaptive and scalable and enhance developer productivity.

Santhosh Shanmugam

Santhosh Shanmugam works as a senior data scientist on Uber's Marketplace team.

Andrea Pasqua

Andrea Pasqua is a data science manager overseeing our Intelligent Decisions Systems team at Uber.

Posted by Ye Henry Li, Ritesh Agrawal, Santhosh Shanmugam, Andrea Pasqua

Related articles

Most popular

MySQL At Uber

Adopting Arm at Scale: Bootstrapping Infrastructure

Adopting Arm at Scale: Transitioning to a Multi-Architecture Environment